A Rare Glimpse into the World of Katana Sword-Making with Matsunaga

A Kumamoto Swordsmith

A flurry of steam filled the forge as katana swordsmith Matsunaga Genrokuro scooped clay water onto the amber-red iron of a Japanese samurai sword. Only a moment ago, he’d pulled the blazing-hot metal from under the massive hammer that sent sizzling flares out like an erupting volcano, before cooling it into the muddy concoction. Isn’t that steam hot? I thought as it swirled up to mask Matsunaga’s intently focused gaze.

I have come to witness the traditional swordsmith at work in Kumamoto’s old mining town of Arao. By welcoming curious visitors from Japan and abroad to visit his forge, Matsunaga has opened a window into the mysterious and ancient world of katana sword-making. Here you can watch a portion of the sword-making process, witness a blade’s sharpness in one of his tameshigiri (“test cut”) sword demonstrations, and browse Matsunaga’s collection of antique swords and samurai armor.

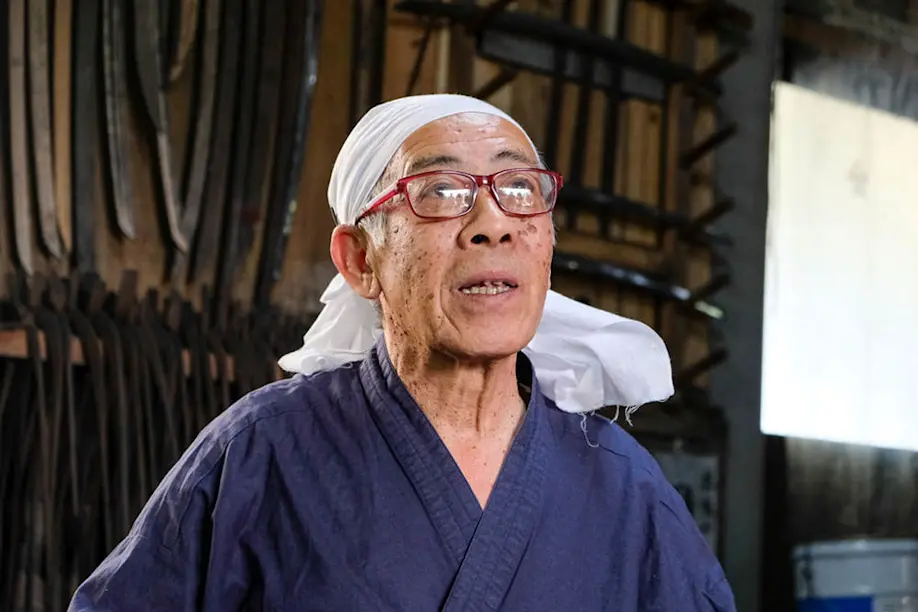

This particular visit is my second to the swordsmith’s forge, the first being over a year ago. When I show up, Matsunaga’s eyes light up with recognition. I’m surprised he remembered.

Like last time, he’s wearing pressed, blue work clothes and red frame glasses — almost the same shade as the smoldering red embers in his forge. Again I am led back into his forge and back into the time-honored heritage of katana sword-making, one that has been virtually unchanged since the days of the samurai.

Though this ancient katana sword-making craft could have ended with the 1868 Meiji Restoration, which abolished the once-powerful samurai rule, the traditional techniques miraculously survived and continue to shine in the hands of passionate craftspeople.

Matsunaga has been refining his sword-making practice for most of his lifetime. His early fascination with the katana sword started in his youth while training in sword-wielding martial arts, which led him to an interest in the sword-making craft itself. As a young adult, he spent five years learning the basics, passing several tests to verify his abilities before he set off on his own to refine his technique over the next four decades.

I follow Matsunaga back to his workshop, where there are several swords in various stages of completion. Don't worry about missing any points of the sword-making process during your visit, as informational English handouts helpfully outline each of his steps. I watch from a safe social distance as Matsunaga picks up a sample of heavy, glittering iron called tamahagane — one of the first stages of the sword-making process. In order to make this particular tamahagane, iron fragments are collected from the Arao coastline, then smelted with charcoal to create the carbon-rich iron suitable for making a katana sword. I never cease to be amazed at how natural, raw materials can be molded into something so refined as the katana.

About nine kilograms of tamahagane is broken, rearranged, and wrapped in Japanese washi paper, then fired at a blazing 1,700 degrees Celsius in a pine charcoal-heated forge. Next, Matsunaga will demonstrate the iconic “folding” highlight of the sword-making process. Following the first quench, the iron will be reheated, folded, hammered, then re-fused between ten to fifteen times until it becomes a consistently refined piece of steel weighing between 800 grams and 1 kilogram — a fraction of its original weight.

We wait patiently as the smoldering pine charcoal heats one of the swords. Only experience tells the swordsmith when the iron is ready to hammer. I pay close attention, as my previous visit has taught me that Matsunaga’s move to the machine-powered hammer will be sudden and swift. He’s kind enough to warn me before it happens, and within moments, the bright-hot metal is pulled from the forge and immediately served under the pounding hammer, sending sparks bursting in every direction.

Only when the metal meets Matsunaga’s standards of consistency and refinement is the steel slowly hammered out into the shape of a katana sword. Matsunaga demonstrates this firing process, called sunobe, on another sword he is working on.

In total, the swordsmith’s work takes roughly two weeks of hammering, shaping, and testing the sharpness of the sword before it is handed off to the next specialist to add their finishing touches. The complete production of a single katana takes approximately three months to complete, from collecting raw iron sand from the Arao coastline to the collaborative final stages of polishing, engraving, inlaying, and embellishment work by other specialized craftspeople. This laborious process is a prime example of how tradition is carried out by a handful of artisans who refuse to let the precision techniques and knowledge fall to the wayside.

After the sword-making demonstration, you may be lucky enough to witness Matsunaga’s expert tameshigiri sword-cutting performance. This is one of the final tests the sword will undergo before it is handed off to the next craftsperson.

Matsunaga re-emerges in a fresh white outfit in the tameshigiri demonstration area outside the forge. He then mounts rolled bamboo mats on a post. (There’s hand sanitizer available in a corner of the arena, but the extra social distancing required for Covid-19 prevention will already keep you at a doubly safe distance as you watch the master swordsmith verify the sharpness of his sword.) The blade slices effortlessly through the bamboo mats, which instantly tumble into a pile of elegant slivers on the ground.

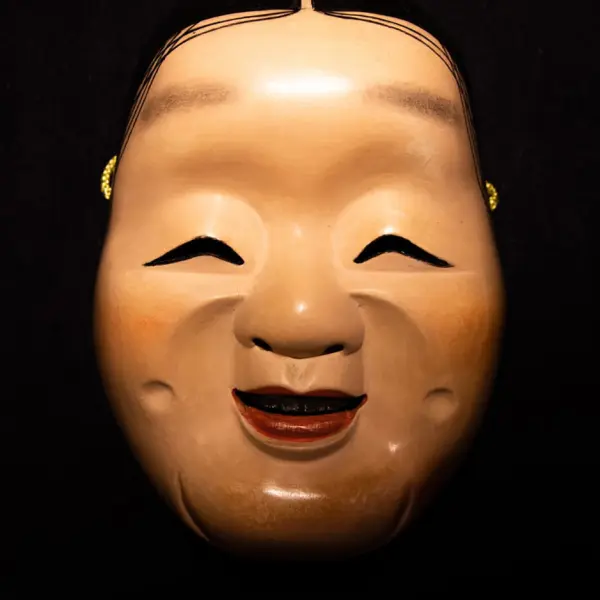

Matsunaga’s private collection of antique samurai swords and armor is an impressive testament to the timeless heritage linked to the katana sword. His blades represent diverse styles and lengths, from modestly designed katana to long, unwieldy spears used in battle on horseback. The armor will also give you an idea of how the samurai warriors protected themselves from enemy attacks. Admiring the decorative metal pieces and thickly woven layers, I can only imagine how heavy it must have been for the feudal warrior to wear as he headed into battle.

The time-honored craft of katana sword-making may have dwindled since the end of Japan’s feudal samurai era, but the unwavering passion of craftspeople like Matsunaga has successfully carried this unbroken tradition into the modern world. Whether or not you happen to be a sword enthusiast, a visit to the swordsmith is a pleasure that everyone should experience at least once. As Matsunaga and I part ways for the second time, I already know that this won’t be my last call to the swordsmith in Kumamoto, nor my final glimpse into the ancient world of katana sword-making.

Note: This blog post was written during a time when preventive measures for COVID-19 were being undertaken. These measures are expected to be relaxed going forward.

Mika Senda

Mika is a writer for Voyapon.com and Lostin-Kyushu.com. In 2018, she made her way from her hometown in Canada to the countryside of Oita Prefecture. Since then, she's been exploring the tradition, art and culture of inaka life, and most likely sitting in an onsen right now.

Shonenji Temple in Takachiho: A fascinating past and present

Shonenji Temple in Takachiho: A fascinating past and present Karatsu, Imari and Arita: A Trip to Discover Saga Ceramics

Karatsu, Imari and Arita: A Trip to Discover Saga Ceramics Immerse Yourself in the History and Culture of Japan’s Samurai Warriors at Marutake Sangyo

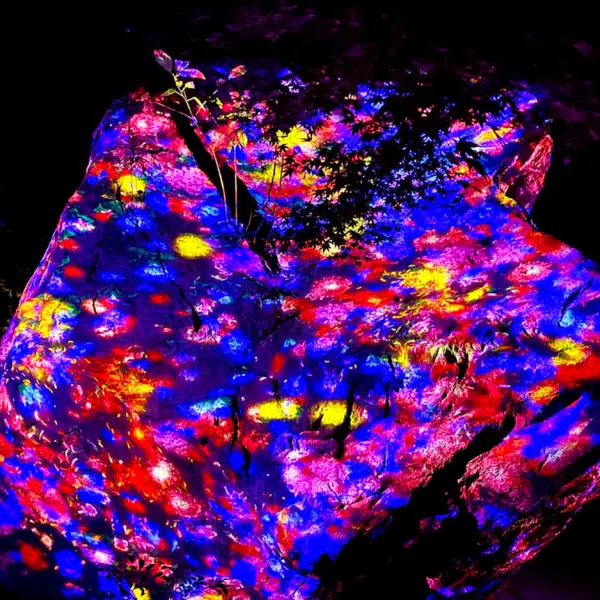

Immerse Yourself in the History and Culture of Japan’s Samurai Warriors at Marutake Sangyo TeamLab breathes history at Mifuneyama Rakuen in Saga

TeamLab breathes history at Mifuneyama Rakuen in Saga Spooky Castles, Wild Boar, Wax, and Kagura!

Spooky Castles, Wild Boar, Wax, and Kagura! Koishiwara Pottery: From Climbing Kilns to Flying Dot Patterns

Koishiwara Pottery: From Climbing Kilns to Flying Dot Patterns A Rare Glimpse into the World of Katana Sword-Making with Matsunaga, a Kumamoto Swordsmith

A Rare Glimpse into the World of Katana Sword-Making with Matsunaga, a Kumamoto Swordsmith The Ancient Tradition of Ceramics Found in Saga Prefecture

The Ancient Tradition of Ceramics Found in Saga Prefecture Taketa, Oita: An alluring artscape

Taketa, Oita: An alluring artscape Samurai Road, Garden, and Dessert

Samurai Road, Garden, and Dessert