Koishiwara Pottery

From Climbing Kilns to Flying Dot Patterns

Koishiwara pottery is recognizable by its distinctive decorations showing the contrast between the dark clay and the white clay, such as chattered spiral, brushstrokes, combed lines, or finger strokes. The original Koishiwara potters were all farmers by trade, whose clay preparation was particularly vulnerable to the whims of nature. Likewise, the tools they used to decorate the mostly household wares were simple objects such as clock springs, brushes, combs, and their own fingers.

During the Edo and Meiji periods, Koishiwara pottery was mainly destined for domestic use, such as water containers, food jars, and pouring vessels, sold informally in the nearby city of Hita. These farmer potters continued to produce wares alongside their main agricultural activities until the 1960s when a growing interest in Japanese folk arts attracted government subsidies, media attention, and increased sales. By then, almost all Koishiwara potter households could afford to focus on their craft full-time.

In 1975, Koishiwarayaki was officially designated as the first traditional handicraft in Japan. In 2017, as the region was just starting to rebuild following devastating floods and landslides, 16th-generation Koishiwara potter Zenzo Fukushima was named a Living National Treasure.

The comprehensive Koishiwarayaki Traditional Industry Museum traces the history of the craft and exhibits highlights through its extensive collection of Koishiwara pottery from pre-modern times to the present. Twice a year, in May and October, a pottery festival is held to showcase the region’s wares. Even Koishiwara’s Roadside Station is built in the shape of a traditional climbing kiln.

There are currently 43 active Koishiwara kilns clustered within Toho village in Fukuoka prefecture, and Koishiwara pottery continues to evolve with each new generation of potters.

I visit Marudai kiln, nestled in the mountains not far from the famous Gyoja Cedar forest. Ota Kazuya, a 15th-generation Koishiwara potter who married into his wife’s Marudai household, has everything he needs on his property within a few steps of his family home. His studio is the size of a barn, with large windows framing dry branches behind him, makeshift furniture, and shelves of drying bowls and dishes.

Ota-san holds a small flat rod in one hand as the dish spins steadily around the wheel between his legs. Within seconds, a chattered spiral of toothlike incisions appears through the white slip on the wet plate. This is tobikanna, one of the most characteristic patterns of Koishiwara pottery.

As Ota-san demonstrates each characteristic decoration technique, his hands move deftly around the clay, transforming a shapeless mound into an artfully crafted ware in minutes. He remembers watching his father in awe and helping out with the kiln as a boy, but he didn’t start making his own pottery until he was 20. “It was much more complex than I imagined,” he says.

Behind his workshop, he shows us the gas-powered kiln he uses to fire the pots. The unglazed wares are first bisque fired at 1000°C for 15 hours to harden the fragile clay. Then, once glazed and decorated, they are fired at 1250°C for another 20 hours. Currently, he is experimenting with different glazes, mixing wood ash, straw ash, iron, and oxidized copper to obtain various hues of gray, reddish-brown, and green. Inside the shed beside the samples are several discarded pieces where the glaze has melted into unruly gobs at the base. Once a month, several hundred wares are fired together inside the gas kiln.

Back outside, Ota-san shows us the household’s private climbing kiln. These long and sloping, brick-layered noborigama are famously rare traditional kilns that are heated exclusively by firewood, so the temperature is much harder to control. Marudai’s climbing kiln has three deep chambers, with a little square window at the top to monitor the temperature over time with a roughly potted cup.

Ota-san tells us that the same ware will be of a slightly different color, depending on whether it is fired in the gas kiln or in the climbing kiln. For comparison, he shows us the darker, more rusty color and texture of a large bowl fired in the less predictable noborigama. Refining and perfecting every detail of a carefully crafted piece is a game of trial and error, skill, and patience.

Almost as impressive as Marudai’s climbing kiln is their family house, tea room, and shop, all in a traditional building constructed with a thatched roof and tied beams in the artisanal gassho-zukuri architectural style. Inside, dainty teacups are exhibited alongside giant pots and vessels, as if in a living museum. The shop displays affordable kitchenware items, with a central table highlighting wares fired in the noborigama.

I find myself curiously drawn to another table of “imperfect” sale items. I pick up a wide-rimmed teacup with a deep coffee-brown color and creamy hakeme pattern. After I search in vain for its said imperfection, Ota-san points out a tiny nick on the cup’s beige inner glaze. This one-of-a-kind cup is half the price of identical-looking teacups for sale on the main shelf. I am happy to buy it and take home an authentic piece of Koishiwara pottery.

My next stop is Tsurumi kiln, located further down the mountain off Route 211 along the Ohi river. The traditional house storefront welcomes us with a friendly, modern design as we step directly into a brightly lit boutique of colorful wares.

In his early forties, Tsurumi’s master potter is Wada Yoshihiro, a good-looking, style-conscious, second-generation Koishiwarayaki craftsman who also studied at a traditional crafts school in Kyoto. His hands are just as deft at throwing the clay at the wheel, but his forms and designs are notably more contemporary.

He demonstrates crafting a typical mug, pleasingly rounded and evenly bulging like an oversized egg. After basting it in white slip, he uses a standard brush to trace an even brown line around the girth of the vessel. Then he picks up a curved fork-like rod but uses only one of its sharp points to incise the clay with a loose spiral of dots. This is dot-tobikanna, a playful riff on Koishiwarayaki’s characteristic tobikanna, and a signature decoration of Tsurumi kiln.

On another whitewashed mug, he paints billowing curves that run into the rims. “My original idea was to draw a Holstein cow pattern for the year of the ox, but people just saw clouds, so now I call it the cloud series,” Wada-san explains. Their most popular color combination is black and white, but one of their best-selling lines of mugs also features pink, orange, and yellow, as well as pastel blue and green stripes. Clearly, this is an entirely new generation of Koishiwara pottery.

While the potter feels proud and privileged to inherit the kiln from his father, who founded Tsurumi-gama in 1974 and is now in his eighties, Wada-san also feels a heavy responsibility in treading the careful line between Koishiwara tradition and eye-candy innovation.

Nonetheless, young Wada-san firmly holds the reins to the kiln’s renewed future: Tsurumi-gama reaches out to potential new customers and fans on social media; an online shop is in the works through their comprehensive and engaging website; hands-on pottery workshops are available to visitors, and their on-site café serves food and drink on Tsurumi wares as a way to showcase their designs in a casual culinary context.

If Marudai and Tsurumi represent the wide range of styles in the ongoing evolution of Koishiwara pottery, Ota-san and Wada-san share a common modesty in crafting their wares. When asked what they liked to make most, both potters responded alike: everyday use items, cups, dishes, bowls, the very same kind of vessels people have been using for centuries.

Cherise Fong

Originally from San Francisco, I arrived in Tokyo with my bike and my backpack one rainy day in summer. Since then, I travel through the archipelago by bicycle, train and boat, often to the rhythm of taiko and shinobue, always looking for new paths and unique perspectives.

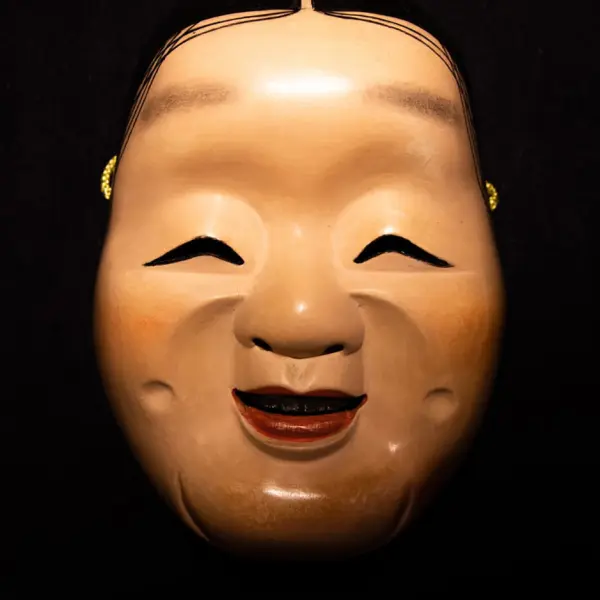

Shonenji Temple in Takachiho: A fascinating past and present

Shonenji Temple in Takachiho: A fascinating past and present Karatsu, Imari and Arita: A Trip to Discover Saga Ceramics

Karatsu, Imari and Arita: A Trip to Discover Saga Ceramics Immerse Yourself in the History and Culture of Japan’s Samurai Warriors at Marutake Sangyo

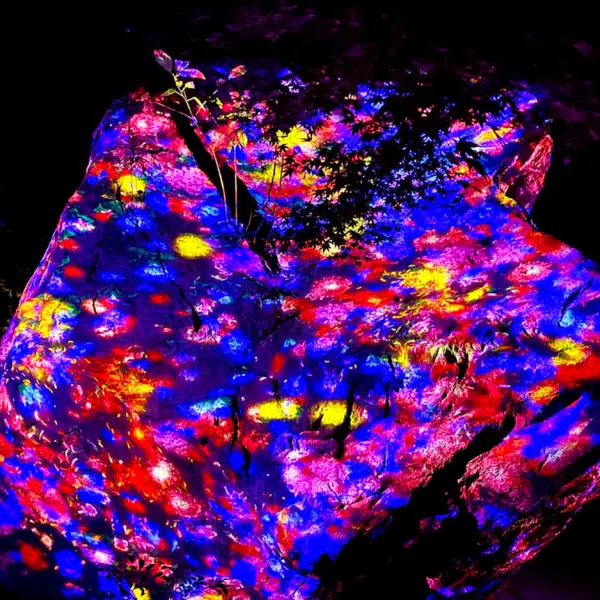

Immerse Yourself in the History and Culture of Japan’s Samurai Warriors at Marutake Sangyo TeamLab breathes history at Mifuneyama Rakuen in Saga

TeamLab breathes history at Mifuneyama Rakuen in Saga Spooky Castles, Wild Boar, Wax, and Kagura!

Spooky Castles, Wild Boar, Wax, and Kagura! Koishiwara Pottery: From Climbing Kilns to Flying Dot Patterns

Koishiwara Pottery: From Climbing Kilns to Flying Dot Patterns A Rare Glimpse into the World of Katana Sword-Making with Matsunaga, a Kumamoto Swordsmith

A Rare Glimpse into the World of Katana Sword-Making with Matsunaga, a Kumamoto Swordsmith The Ancient Tradition of Ceramics Found in Saga Prefecture

The Ancient Tradition of Ceramics Found in Saga Prefecture Taketa, Oita: An alluring artscape

Taketa, Oita: An alluring artscape Samurai Road, Garden, and Dessert

Samurai Road, Garden, and Dessert